OKRs: Complete Guide to Objectives and Key Results

TL;DR: OKRs in 60 Seconds

- OKR stands for Objectives and Key Results, a goal-setting framework used by Google, Intel, and thousands of product teams worldwide

- Objectives = What you want to achieve (qualitative, inspiring, time-bound)

- Key Results = How you measure success (quantitative, specific, outcome-based)

- Formula: "We will [Objective] as measured by [Key Results]"

- 3-5 objectives per quarter maximum, each with 2-4 key results

- 70-80% achievement = success (OKRs are stretch goals, not commitments)

- Review weekly, score quarterly, retrospect before planning the next cycle

OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) are a goal-setting framework that helps product teams focus on outcomes instead of outputs. Developed at Intel in the 1970s and later adopted by Google, LinkedIn, Twitter, and thousands of organizations worldwide, OKRs have become the standard for aligning teams around measurable goals. In my coaching work with product teams across Europe, I have seen OKRs transform how organizations set priorities, measure progress, and create accountability. This guide covers everything you need: what OKRs are, how to write them, a complete planning process with meeting templates, common mistakes, and a maturity model to help your practice evolve over time.

What Are OKRs?

OKR stands for Objectives and Key Results. It is a goal-setting framework that connects ambitious qualitative goals (Objectives) with specific quantitative measures of success (Key Results). The framework was created by Andy Grove at Intel in the 1970s as a way to align engineering teams around shared priorities. In 1999, John Doerr introduced OKRs to Google when the company had just 40 employees. Today, Google still uses OKRs across the entire organization, and the framework has been adopted by companies of every size, from two-person startups to enterprises with thousands of employees.

The framework has two components:

- Objectives: Qualitative statements describing what you want to achieve. They should be ambitious, inspiring, and time-bound (usually quarterly). A good objective is concrete enough to visualize success but ambitious enough that achieving it would feel like a meaningful step forward. Think of objectives as the direction your team is marching in.

- Key Results: Quantitative metrics that measure whether you achieved the objective. Each objective typically has 2-4 key results. They must be specific, measurable, and focused on outcomes rather than activities. Key results answer the question: "How would we know we succeeded?"

The OKR formula is simple: "We will [Objective] as measured by [Key Results]."

For example: "We will become the most trusted tool for daily task management (Objective) as measured by increasing daily active users from 10K to 25K, improving 7-day retention from 35% to 50%, and reducing time-to-first-value from 5 minutes to 2 minutes (Key Results)."

The power of OKRs comes from their simplicity. They force teams to focus on outcomes rather than outputs, and they create alignment across the organization by making goals transparent. When every team can see what every other team is working toward, duplication drops and collaboration rises. They also create a shared language for priority conversations. Instead of debating features, teams debate outcomes.

"Vanity metrics make us feel good, but they don't move the needle." (Ben Yoskovitz, author of Lean Analytics)

This is why Key Results must be outcome metrics, not activity metrics. "Launch feature X" is a task. "Increase 7-day retention from 35% to 50%" is a Key Result. The difference matters because tasks can be completed without creating value. A team can launch ten features and move zero business needles. Key Results only improve when real value is delivered to users or the business.

There are two types of OKRs you should understand. Committed OKRs are goals the team agrees to deliver at 100%. They represent the baseline expectation. Aspirational OKRs (sometimes called "moonshots") are stretch goals where 70% achievement is considered success. Google uses roughly a 50/50 split. In my coaching experience, teams new to OKRs should start with committed OKRs only and add aspirational ones once the team understands the scoring system and has built trust that partial achievement is not punished.

OKRs work best when connected to your broader strategic context. Start by defining your product vision so that every quarterly OKR clearly traces back to a larger purpose. Then ensure you are aligning OKRs with your product strategy so that quarterly goals move the strategic needle rather than just keeping teams busy. The vision tells you where you are going. The strategy tells you how you will get there. OKRs tell you what you will accomplish this quarter to make progress on that strategy.

OKR Examples for Product Teams

The best way to understand OKRs is to see them in action. Here are practical OKR examples you can adapt for different focus areas. Notice how each Key Result is specific, measurable, and has a clear baseline and target. These are the patterns I see in the best OKR-driven teams.

| Focus Area | Objective | Key Results |

|---|---|---|

| User Engagement | Become the go-to tool for daily task management | KR1: Increase DAU from 10K to 25K KR2: Improve 7-day retention from 35% to 50% KR3: Reduce time-to-first-value from 5min to 2min |

| Product Quality | Deliver a rock-solid user experience | KR1: Reduce critical bugs from 12 to 3 KR2: Improve app store rating from 3.8 to 4.5 KR3: Decrease page load time from 3s to 1.5s |

| Revenue Growth | Establish a sustainable revenue engine | KR1: Grow MRR from 50K to 100K KR2: Increase paid conversion from 2% to 5% KR3: Reduce monthly churn from 8% to 4% |

| Customer Success | Make customers feel supported at every touchpoint | KR1: Increase NPS from 32 to 55 KR2: Reduce average support resolution time from 48h to 12h KR3: Grow self-service resolution rate from 40% to 70% |

| Team Velocity | Ship faster without sacrificing quality | KR1: Reduce average cycle time from 14 days to 7 days KR2: Increase deployment frequency from 2x/month to 2x/week KR3: Maintain code review turnaround under 4 hours |

Good vs. Bad OKRs: Spot the Difference

The difference between a good OKR and a bad one often comes down to one thing: whether the Key Result measures an outcome or an activity. Here are three common patterns I see teams get wrong, along with the fix.

| Bad OKR | Why It Fails | Better Version |

|---|---|---|

| O: Improve our product KR: Launch 5 new features | Objective is vague. KR measures output (launches), not outcome (user value). You could launch 5 features nobody uses. | O: Deliver a product users recommend to colleagues KR: Increase NPS from 30 to 50 |

| O: Be more data-driven KR: Set up a dashboard | Objective is generic. KR is a task (setting up a dashboard), not a measurable outcome. The dashboard could sit unused. | O: Make every product decision backed by evidence KR: Reduce decisions overturned by stakeholders from 40% to 10% |

| O: Grow revenue KR: Run 3 marketing campaigns | No baseline or target on the objective. KR is an activity that may or may not impact revenue. | O: Build a predictable revenue growth engine KR: Grow MRR from 80K to 120K |

| O: Increase customer satisfaction KR: Send satisfaction survey to all users | Objective is too broad. KR measures activity (sending surveys), not the satisfaction score itself. | O: Become the tool customers cannot imagine working without KR: Increase CSAT from 3.2 to 4.5 out of 5 |

For more inspiration across different industries and team types, check out real-world OKR examples from companies like Google and Netflix.

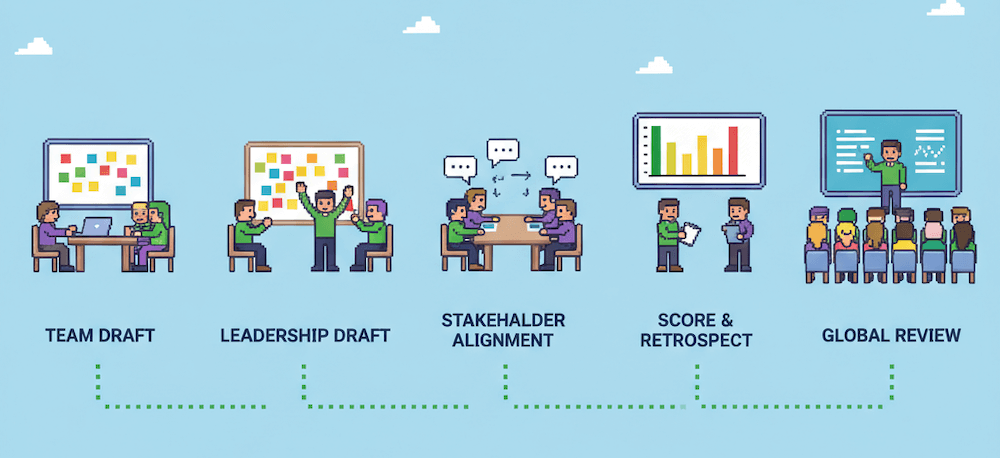

The OKR Planning Process (5 Steps)

I have seen OKR planning drag on until the end of the first month of a quarter. That is obviously too late. Teams lose up to six weeks of execution time per quarter when planning is not structured. A well-defined process ensures you finish planning on time so you can start execution with well-aligned OKRs from day one.

"If every quarter it takes six weeks to have OKRs ready, you're losing six weeks of execution." (Christian Strunk)

The following process is based on my experience coaching product teams at multi-product companies. If your organization is simpler, cherry-pick the parts that apply. The key is to have a process at all rather than letting planning happen ad hoc. Most planning failures come not from using the wrong process but from having no process.

Step 1: Create Your First OKR Draft (Engineering Team)

Teams create a draft without knowing exactly whether previous OKRs will be achieved. If you foresee some objectives not being achieved, prioritize them in the draft. This step should happen 3-4 weeks before the quarter ends.

The goal is to look into the next quarter with your team. What will be high priority? What needs to be fixed? What do customers want? In my coaching experience, the best drafts come from teams who start with customer problems rather than internal wishlists. When a team begins by asking "what are our users struggling with?" the resulting OKRs are almost always more impactful than when they start with "what features should we build?"

Meeting Setup:

- Owner: Product Manager or Team Lead

- Attendees: Team + 1-2 key stakeholders

- Duration: 1.5 hours

Preparation (send 1 week in advance):

- Create a new OKR document using last quarter's format and share it with the team

- Include the current quarter's OKR scores (even if estimated) so the team sees what is carrying forward

- Ask attendees to prepare 2-3 suggestions each for the next quarter, based on customer feedback, data trends, and strategic priorities

- Share any relevant user research findings or customer complaints that could inform priorities

Agenda:

- Quick review of current quarter results and carry-over items (15 min)

- Round-robin idea sharing: each person presents their suggestions (30 min)

- Group discussion and priority voting (30 min)

- Write first draft of 2-4 objectives with Key Results (15 min)

Step 2: Create Your First OKR Draft (Leadership Team)

The leadership team discusses priorities for the next quarter, taking previous OKRs into consideration. Choose who should participate wisely. Too many people at an offsite makes teams unproductive. I recommend a maximum of 8-10 people for this session.

Meeting Setup:

- Owner: Team/Tribe/Chapter Lead

- Attendees: Team Leads and Product Managers

- Duration: 2 hours

Process:

- Each member writes priorities on sticky notes (Objectives + Key Results), 10 min

- Present ideas in front of the group (no discussions, pitch only), 30 min

- Group and cluster similar ideas on a whiteboard, 10 min

- Review and discuss priorities as a group, 30 min

- Team voting on priorities (everyone gets 3 votes), 10 min

- Final review of high-level priorities and assignment to owners, 20 min

In my coaching experience, the biggest risk in this step is leadership creating OKRs in isolation. The best outcomes happen when leadership drafts are informed by bottom-up team input from Step 1. Top-down alignment works when it meets bottom-up reality. If leadership OKRs contradict team-level insights from Step 1, that is a signal to investigate further, not to override the team.

Step 3: Share and Adjust OKRs With Stakeholders

Before sharing OKRs company-wide, start with your key stakeholders. Some teams have more dependencies than others. If your company uses value streams like Spotify, squads present their OKRs to the whole tribe.

This step is critical for catching misalignment before it becomes a problem. A common scenario: Team A plans to deprecate an API endpoint that Team B depends on for their Q1 objective. Without Step 3, both teams discover the conflict mid-quarter. With Step 3, they negotiate a timeline that works for both.

Follow up with key stakeholders, share feedback with your team, and adjust if needed. This session is for gathering feedback, not making decisions and changing everything. In my coaching experience, the teams that handle this step well treat it as a negotiation: they listen to feedback, push back where needed, and document agreements so there is no ambiguity going into the quarter.

Run 2-3 short stakeholder alignment sessions (30 minutes each) rather than one large meeting. Focus each session on the specific dependencies between your team and the stakeholder's team.

Step 4: Review and Retrospect the Current Quarter

As you approach the end of the quarter, review outcomes and retrospect. This step runs in parallel with Steps 1-3 during the overlap period between quarters. Do not skip this step. The retrospective is where learning happens, and without learning, your OKR practice does not improve.

Measuring OKR Achievement:

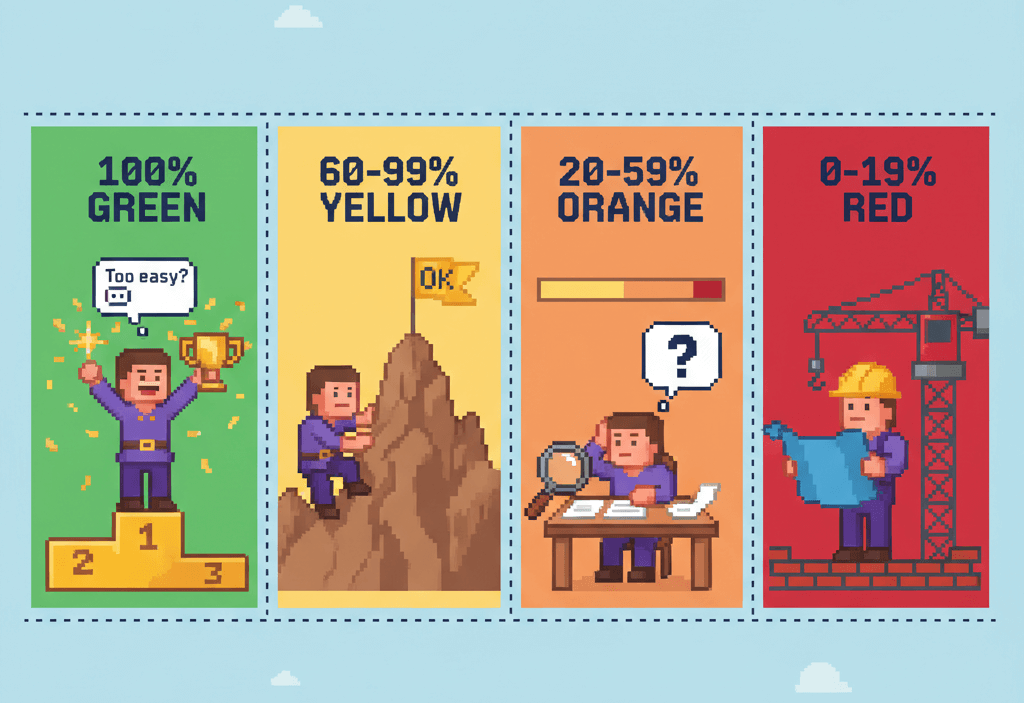

If you defined OKRs well, the objective is achieved when all key results are achieved. But what if they are not? My teams use a percentage rating from 0-100% with a color code that I call the Coaching Scorecard:

- Green (100%): Fully achieved. Celebrate. Then ask: was this ambitious enough? If a team hits 100% on every OKR, the goals were too easy.

- Yellow (60-99%): Solid progress, worth celebrating. Carry remaining gap into next quarter if still strategically relevant.

- Orange (20-59%): Partially achieved. Needs a deep retrospective. Were the Key Results realistic? Did priorities shift mid-quarter?

- Red (0-19%): Missed. Something went fundamentally wrong. Root cause analysis required. Was this the right objective? Did the team have the resources and skills needed?

Remember: 70-80% achievement is considered successful for aspirational OKRs. Google famously targets 70%. If your team consistently hits 100% on every OKR, your goals are not ambitious enough and you are leaving growth on the table.

Running the OKR Retrospective:

Retrospectives help you understand why key results were or were not achieved. Spend two hours reviewing the previous three months. This is not a blame session. It is a learning session. My teams typically use one of these formats:

- Start, stop, continue: What should we start doing, stop doing, and keep doing next quarter?

- Sad, mad, glad: What made us sad, what frustrated us, and what are we proud of?

- Went well, to improve, action items: Data-driven review with concrete next steps.

Use an external facilitator (someone outside the team) for best results. The facilitator can ask uncomfortable questions that team members avoid. They also prevent the most senior person in the room from dominating the conversation, which is a pattern I see in nearly every unfacilitated retrospective.

Step 5: Review and Present OKRs Globally

At the beginning of the new quarter, every team should know their priorities. Share results from the previous quarter and plans for the new quarter across the company. This creates transparency and helps teams spot last-minute conflicts or collaboration opportunities.

Check one last time if anything has changed that might impact your priorities. Last-minute changes happen at both team and company levels. A major customer loss, a competitor launch, or a market shift can make carefully planned OKRs obsolete overnight.

Many companies use All-Hands meetings to share company and leadership OKRs. This provides transparency and focus for the whole organization. I recommend using a master sheet containing one or two slides from each team so everyone can see the full picture at a glance. Keep the presentation focused: each team gets 5 minutes maximum to share their top 2-3 objectives and explain why they chose them.

After the All-Hands, make all OKRs accessible in a shared document or tool. Transparency is one of the core principles of OKRs. If teams cannot see each other's goals, the alignment benefit disappears.

The OKR Scoring System: The Coaching Scorecard

Scoring OKRs consistently is harder than it sounds. Without a clear system, quarterly reviews become subjective debates where teams argue about whether "mostly done" counts as success. I developed the Coaching Scorecard after watching teams struggle with vague "we did okay" assessments quarter after quarter. Without a consistent scoring system, teams cannot compare performance across quarters or identify patterns in what helps and what hurts their execution.

"I don't sleep well if I don't base my strategy and bets on data." (Konrad Heimpel, GetSafe)

The Coaching Scorecard uses four color-coded tiers. Each tier comes with a specific action, not just a judgment. The goal is to turn every score into a learning opportunity.

| Score Range | Color | Meaning | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | Green | Fully achieved | Celebrate, then ask: was this ambitious enough? If every OKR is Green, sandbagging is likely. |

| 60-99% | Yellow | Strong progress | Celebrate progress. Carry remaining gap into next quarter if still strategically relevant. Identify what would have gotten you to 100%. |

| 20-59% | Orange | Partial progress | Retrospect deeply. What blocked progress? Were the Key Results realistic? Did priorities shift? Was the team resourced properly? |

| 0-19% | Red | Missed | Root cause analysis required. Was this the right objective? Did the team have the skills and autonomy needed? What would you do differently? |

The pattern I see across teams is this: most organizations start by treating Red scores as failures and hiding them. Mature OKR organizations treat Red as information. A Red score that leads to a good retrospective is more valuable than a Green score on a sandbagged objective. The point of scoring is not to grade teams. It is to generate the data that makes future planning better.

When scoring, each Key Result gets its own percentage based on how much progress was made toward the target. The Objective score is the average of its Key Results. If you had three Key Results at 80%, 60%, and 40%, the Objective scores at 60% (Yellow). Keep a running record of scores across quarters so you can spot trends. Are certain types of objectives consistently harder? Are specific teams consistently more accurate in their goal setting? These patterns are gold for improving your OKR practice.

Tracking your essential product KPIs alongside OKR scores gives you the full picture of team health. OKR scores tell you about improvement toward specific goals. KPIs tell you about ongoing operational health. Together, they create a comprehensive view of how a team is performing.

Common OKR Mistakes to Avoid

After coaching dozens of teams through OKR cycles, these are the patterns I see most often. Each mistake is common, each is fixable, and each becomes easier to spot with practice.

- Too many objectives. Stick to 3-5 per quarter maximum. I once coached a team with 11 objectives in a single quarter. They achieved meaningful progress on zero of them. Three months of work, zero outcomes moved. When we cut it to 3 objectives the following quarter, they hit Yellow or Green on all three. Focus is not about doing more. It is about doing fewer things that matter deeply.

- Key Results as tasks. "Launch feature X" is a task, not a result. Measure the outcome instead. Ask yourself: what will change in user behavior or business metrics if we do this well? If the answer is "nothing measurable," either the initiative is not worth pursuing or you have not thought deeply enough about the impact you expect.

- No baseline. You cannot improve "engagement" if you do not know the current number. Before setting a Key Result target, measure the baseline. If you cannot measure it yet, your first KR should be establishing the measurement. "Implement engagement tracking and establish a baseline" is a valid Q1 Key Result when no data exists.

- Set and forget. Review OKRs weekly, not just at quarter end. A weekly check-in (15 minutes maximum) prevents surprises and allows course correction when something is trending in the wrong direction. The check-in format is simple: for each Key Result, what is the current number, what is the target, and are we on track? If not, what needs to change this week?

- 100% achievement expected. If you always hit 100%, your goals are not ambitious enough. OKRs are stretch goals by design. Google targets 70% achievement. If leadership punishes anything below 100%, teams will sandbag their goals, setting easy targets they know they can hit. This kills the entire purpose of OKRs.

- Confusing OKRs with KPIs. KPIs are ongoing health metrics you monitor continuously. OKRs are time-bound improvement targets. Your monthly active users count is a KPI. "Increase monthly active users from 50K to 80K by Q2" is a Key Result. Both matter, but they serve different purposes. Confusing them leads to OKRs that never change ("maintain uptime above 99.9%") or KPIs that get ignored because they are not in the OKR document.

- Skipping the retrospective. Many teams rush straight from scoring to planning the next quarter. Without understanding why things went well or poorly, you repeat the same patterns. The retrospective is where organizational learning happens. Dedicate two hours between quarters for a proper retrospective, and keep a record of retrospective insights that can inform future planning.

- Top-down only OKRs. When leadership dictates all OKRs without team input, you get compliance instead of commitment. The best OKR processes combine top-down strategic direction with bottom-up team expertise. Teams closest to the work often know best what is achievable and what matters. Leadership provides the "what" and "why." Teams provide the "how" and the realistic targets.

For a deeper dive into avoiding these pitfalls, read my article on OKR best practices that I have collected from working with scale-up teams.

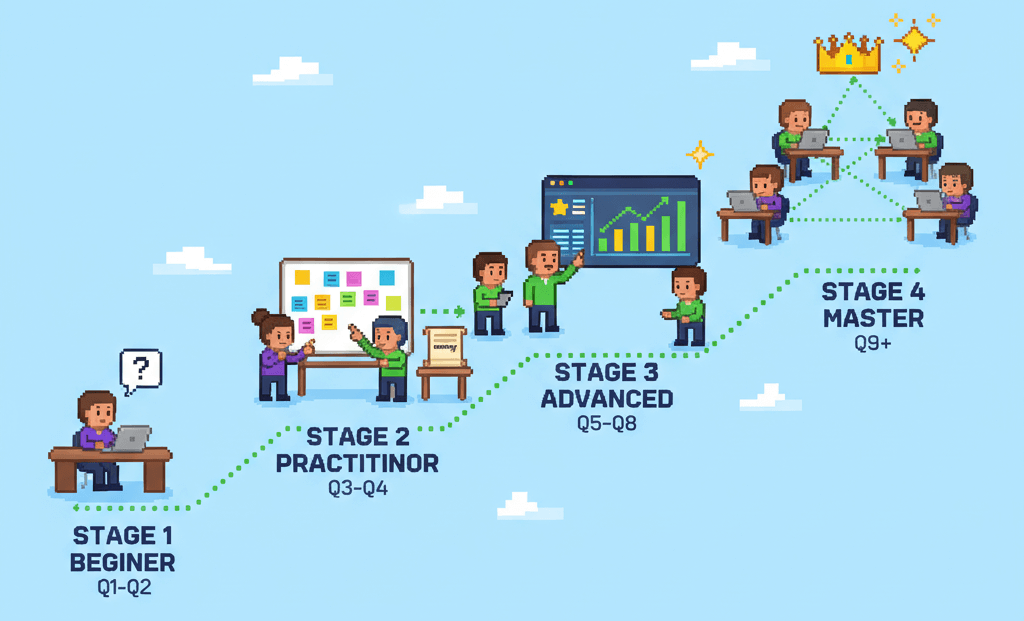

How OKRs Evolve: The Maturity Model

Not every team starts with perfect OKRs. In fact, no team does. The pattern I see across organizations is that OKR practice evolves through four distinct stages, and each stage builds on the one before it. Understanding where you are helps you focus on the right improvements instead of trying to implement everything at once. Trying to skip stages is like trying to run before you can walk. It does not work, and it creates frustration that makes teams want to abandon the framework entirely.

"Just because you can track something doesn't mean you should." (Adam Greco)

Stage 1: Beginner (Quarters 1-2)

Teams are learning the format. Objectives might read like tasks. Key Results might not be measurable. Some team members are skeptical. That is all normal and expected.

What to focus on:

- Get the format right: qualitative Objective, quantitative Key Results

- Limit to 2-3 objectives maximum (fewer is better while learning)

- Run the scoring process even if scores feel arbitrary at first

- Hold retrospectives even if they feel awkward or unfamiliar

- Assign one person per team as the "OKR champion" who keeps the process moving

Diagnostic question: Can every team member explain their team's OKRs without checking a document?

Common pitfall at this stage: Over-engineering the process. Teams buy expensive OKR software, create elaborate scoring rubrics, and schedule too many meetings. Keep it simple. A shared spreadsheet and a weekly 15-minute check-in are enough for Stage 1.

Stage 2: Practitioner (Quarters 3-4)

Teams can write proper OKRs. The planning process has a rhythm. Scoring happens consistently. The main challenge shifts from format to alignment: making sure team OKRs connect to each other and to company strategy.

What to focus on:

- Cross-team alignment (dependencies, shared objectives, conflict resolution)

- Connecting team OKRs to company strategy with a clear line of sight

- Improving the quality of Key Results (outcomes over outputs becomes second nature)

- Building the weekly check-in habit so it becomes automatic, not optional

- Starting to differentiate between committed and aspirational OKRs

Diagnostic question: Do your team's OKRs clearly connect to the company strategy, and can you explain that connection in one sentence?

Common pitfall at this stage: Wanting to give up because "it is extra work." The novelty of Q1 has worn off, but the compound benefits have not fully materialized yet. Push through. Q3-4 is where the investment pays off.

Stage 3: Advanced (Quarters 5-8)

OKRs feel natural. Teams push back on bad objectives without prompting. Scoring conversations are honest and productive. The focus shifts to using OKRs as a strategic tool rather than just a tracking mechanism.

What to focus on:

- Using OKR data to inform strategy conversations and resource allocation

- Experimenting with stretched time horizons (annual OKRs alongside quarterly ones)

- Coaching other teams on their OKR practice (peer learning accelerates improvement)

- Integrating OKR scoring with broader product metrics and business reviews

Diagnostic question: Has your team ever deliberately set an OKR they knew they would not fully achieve because the learning was worth it?

Stage 4: Master (Quarters 9+)

OKRs are embedded in the culture. Teams set ambitious goals without fear of "failure" scores. The framework adapts to the organization rather than the organization adapting to the framework. At this stage, OKRs are not a process people follow. They are how the organization thinks about goals.

What to focus on:

- Simplifying and reducing overhead in the process (you need fewer meetings, not more)

- Using OKRs for cross-functional innovation initiatives that span multiple teams

- Mentoring new teams and new hires on the OKR mindset (not just the format)

- Continuous improvement of the scoring and retrospective process itself

Diagnostic question: Can your organization run an effective OKR cycle without a dedicated facilitator or coach?

Most teams I coach are somewhere between Stage 1 and Stage 2. There is no shortcut through these stages. Each one builds the muscle memory needed for the next. The good news: every team that commits to the process for three to four quarters reaches Stage 2, and from there the momentum carries you forward. For the structural foundations of the framework itself, see the OKR framework fundamentals.

Making OKRs Stick: The Cultural Side

The hardest part of OKRs is not the framework. It is the cultural change required to make them work. In my coaching experience, the technical side (writing OKRs, setting up scoring, running retrospectives) is maybe 30% of the challenge. The other 70% is organizational and cultural. You can have the perfect OKR format and the perfect planning process, and it will still fail if the culture does not support it.

Handling Resistance

Expect resistance. It is normal and it is healthy. People resist OKRs for legitimate reasons: they have seen goal-setting frameworks come and go, they worry about being judged on outcomes they cannot fully control, or they do not see how OKRs differ from the KPIs and targets they already track. These concerns deserve answers, not dismissal.

The most effective response I have found is not to argue. Instead, run one quarter as a pilot with a willing team. Pick a team that is curious and has a leader who is open to experimentation. Let the results speak. When other teams see a pilot team gain clarity and focus, adoption becomes pull rather than push. Forcing OKRs on unwilling teams creates resentment and surface-level compliance without genuine adoption.

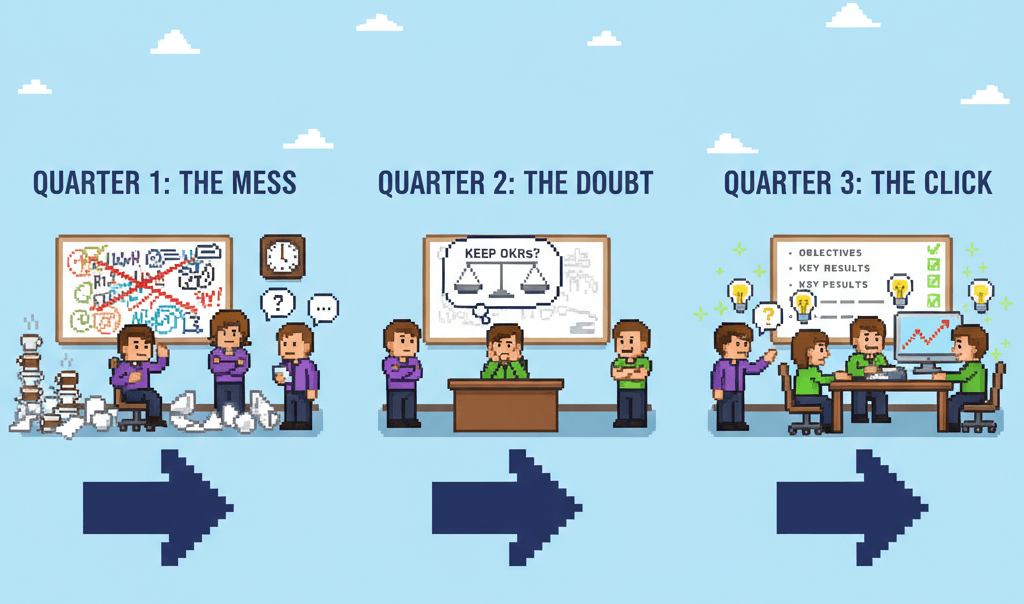

Coaching Through the First Three Quarters

The first quarter is messy. Expect it. Objectives will be too vague, Key Results will be unmeasurable, and the planning process will take twice as long as it should. That is fine. The point of Q1 is not perfection. It is building the habit.

The second quarter is where most organizations want to give up because the novelty has worn off but the benefits have not fully materialized. Teams start saying "this is just extra work on top of our real work." This is the critical moment. If leadership waveres here, the OKR initiative dies.

The third quarter is where the magic happens: teams have enough experience to write good OKRs, scoring conversations are honest, and the planning process feels natural rather than forced.

I once coached a team that wanted to abandon OKRs after Quarter 2 because "it felt like extra work with no payoff." We agreed to try one more quarter with a simplified process: fewer objectives, shorter planning meetings, faster scoring sessions. By the end of Quarter 3, the team asked to keep OKRs permanently because they noticed their strategic conversations had become more focused. Decisions that used to take three meetings now took one. The team lead told me: "I did not realize we were arguing about the same things every week until we had OKRs to anchor us."

When Leadership Does Not Buy In

If leadership treats OKRs as a reporting mechanism rather than a strategic alignment tool, the framework will fail. Teams will game their goals, sandbagging easy wins to look good in quarterly reviews. The spirit of stretch goals disappears when missing a target leads to consequences.

The fix starts at the top. Leadership must model the behavior they want: setting ambitious OKRs for themselves, being transparent about their own misses, and using retrospectives to learn rather than blame. When a VP shares that they scored Orange on their most important objective and explains what they learned, it gives permission for everyone else to be honest too.

If you are a product leader struggling with this dynamic, or if your organization is introducing OKRs for the first time and wants to get it right, consider working with a product coach who can facilitate the organizational change that OKR adoption requires. External facilitation often breaks through internal political dynamics that block honest adoption.

Successful OKR adoption also requires empowered product teams who take ownership of their goals. Without ownership, OKRs become just another top-down mandate that generates compliance instead of commitment. Empowerment means teams choose their own Key Results, have autonomy over how they achieve them, and are trusted to report scores honestly.

Final Thoughts

Not every company works in the same setup. Some companies do not define company OKRs and allow teams to be fully autonomous. Others layer OKRs across company, department, and team levels. The 5-step planning process I outlined is not set in stone. Adapt it to your context, your team size, and your organizational maturity. What matters is that you have a process, not which process you use.

The alignment part only works for companies of a certain size. If the organization becomes too big, focus on high-level company OKRs as a leadership team and let individual teams define their own objectives within that frame. Trying to cascade OKRs through five management layers creates bureaucracy, not alignment.

One final piece of wisdom: do not lose focus. If an objective slips into the next quarter with highest priority, keep focusing on it. If it becomes low priority, stop working on it and move on. Sometimes people are tempted to start with the easiest OKR. I have learned the hard way that you always pay the price later when you defer the hard objectives in favor of quick wins.

OKRs are not magic. They are a structured way to have better conversations about what matters most, measure whether you are making progress, and learn from both successes and failures. The teams that get the most value from OKRs are not the ones with the best format or the fanciest tools. They are the ones that commit to the process, stay honest about their scores, and use every quarter as an opportunity to improve how they work together.

If you want to hear more about OKR planning, check out this podcast episode where I discuss how different companies approach OKR planning and what makes the difference between teams that thrive with OKRs and teams that abandon them.