Qualitative User Research: Methods That Reveal What Users Really Need

TL;DR: Qualitative User Research in 30 Seconds

- What it is: Research methods that explore the "why" behind user behavior through direct human interaction, producing rich contextual insights rather than numerical data

- When to choose qual over quant: When you need to understand motivations, discover unknown problems, or explore new territory where you do not yet know the right questions to ask

- 5 core methods: User interviews, contextual inquiry, usability testing, diary studies, and focus groups

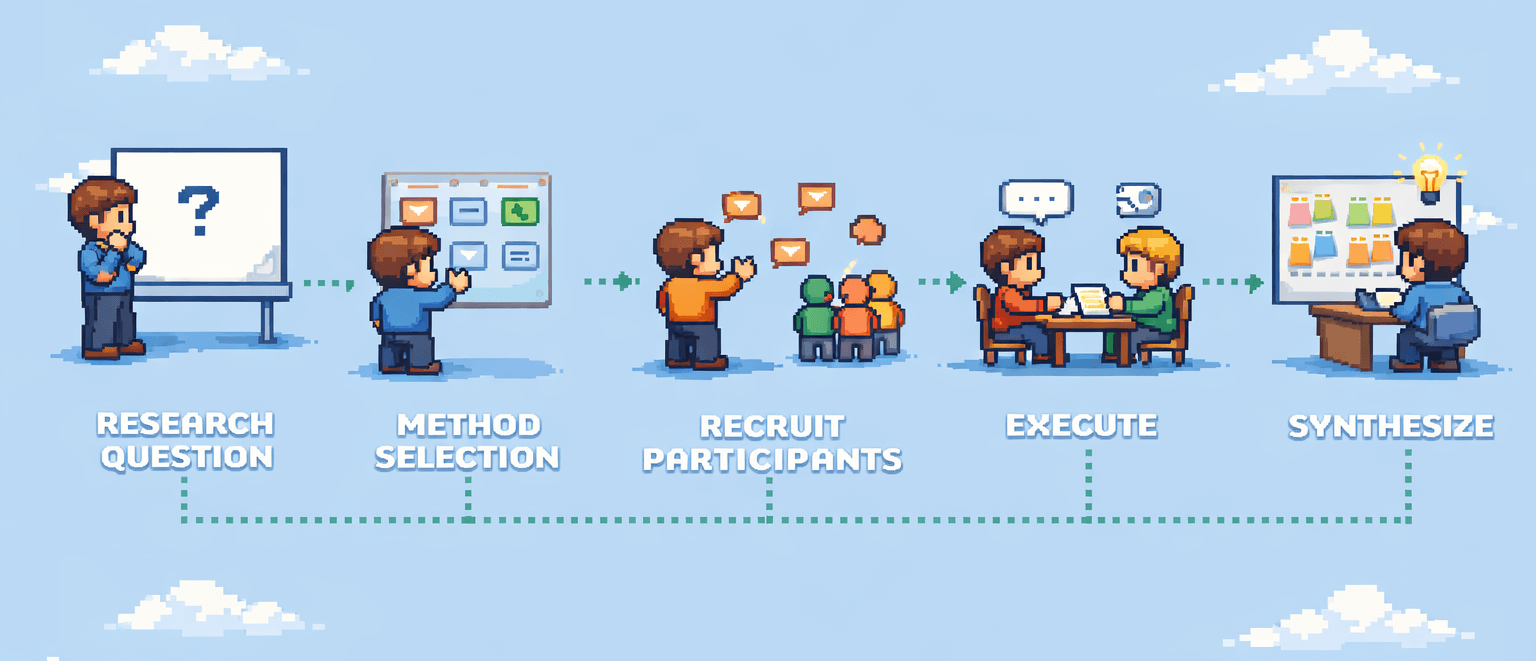

- Planning framework: Research question, method selection, participant recruitment, execution, synthesis

- Key coaching takeaway: The teams that struggle with qualitative research are rarely doing it wrong. They are doing it in isolation, without connecting insights to product decisions.

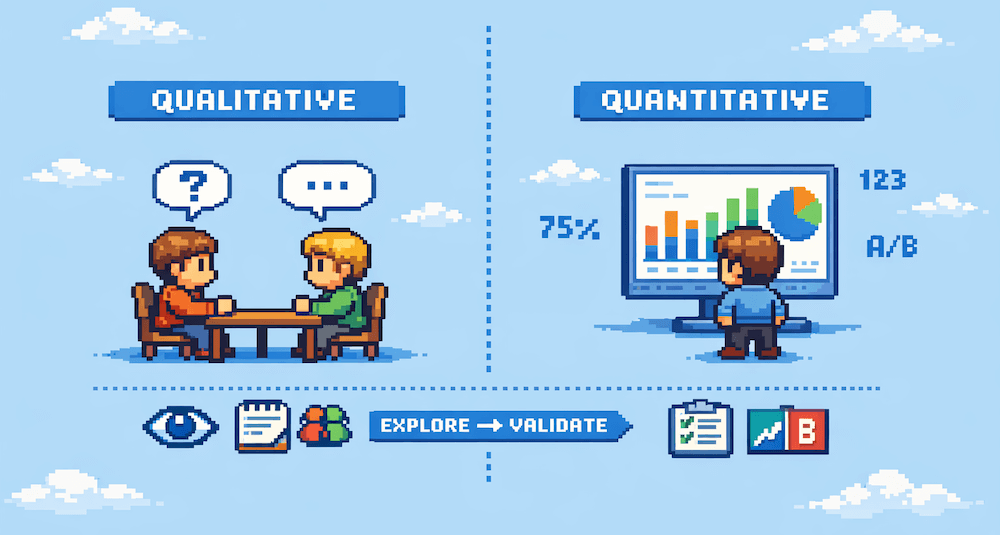

Qualitative user research is the practice of studying user behaviors, motivations, and needs through direct human interaction, using methods like interviews, observations, and usability tests to generate rich contextual insights. Unlike quantitative research that measures "how many" and "how much," qualitative research answers "why" and "how," giving product teams the depth of understanding needed to build solutions that genuinely solve user problems.

Most product teams know they should talk to users. Fewer know how to choose the right qualitative method for their specific situation. Even fewer know how to synthesize what they hear into product decisions that hold up under scrutiny. The result is a gap between research activity and research impact: teams run interviews but still ship features based on assumptions.

This guide covers five core qualitative methods, a decision framework for when to use qualitative versus quantitative approaches, and a practical planning process you can start this week.

What Is Qualitative User Research?

Qualitative user research is a category of research methods that collects non-numerical data through direct engagement with users. Instead of counting clicks or measuring completion rates, qualitative research captures stories, emotions, workarounds, and the reasoning behind user behavior. The output is not a spreadsheet. It is a deeper understanding of the people you are building for.

The distinction between qualitative and quantitative research matters because each answers fundamentally different questions. Quantitative research tells you that 40% of users drop off during onboarding. Qualitative research tells you they drop off because the setup wizard asks for information they do not have yet and they feel embarrassed admitting it. Both facts matter. Only one explains the problem well enough to fix it.

"Design thinking focuses on building empathy, defining problems, working on solutions and testing." - Christian Strunk

Building empathy is where qualitative research earns its place. Numbers can tell you what is broken. Conversations with real users tell you what it feels like to encounter that broken experience. That emotional layer changes how teams prioritize, how they frame solutions, and how quickly they move from "interesting finding" to "we need to fix this now."

Qualitative research matters most in these situations:

- Exploring new problem spaces where you do not know enough to write a survey

- Understanding motivations behind behaviors that analytics flag as unusual

- Generating new ideas by discovering needs users themselves have not articulated

- Validating early concepts before investing engineering time in building them

When to Use Qualitative vs Quantitative Research

The most common mistake I see in product teams is treating qualitative and quantitative research as competing approaches. They are complementary. The real skill is knowing which to use when.

| Scenario | Use Qualitative | Use Quantitative | Use Both |

|---|---|---|---|

| New market or user segment | Yes: explore unknown territory | Not yet: you lack the right questions | Qual first, then quant to validate |

| Feature adoption is low | Yes: understand why users avoid it | Yes: measure how widespread | Quant to size the problem, qual to diagnose |

| Prioritizing the roadmap | Partially: understand pain severity | Yes: measure demand across users | Qual for context, quant for scale |

| Evaluating a prototype | Yes: observe confusion and delight | Later: measure task completion rates | Qual during testing, quant post-launch |

| Tracking satisfaction over time | Periodically: deep-dive into scores | Yes: NPS, CSAT at regular intervals | Quant for trends, qual for "why" behind dips |

In my coaching experience, the teams that get stuck are the ones that default to the same method regardless of the question. I worked with a product team that ran user interviews every sprint for six months. They had rich qualitative data about user frustrations. What they lacked was any quantitative evidence of which frustrations affected the most users. They kept building fixes for problems that touched 2% of their user base while ignoring a checkout bug that affected 35%. The interviews felt productive. The product decisions were not.

A simple rule: if you can describe the problem clearly enough to write a survey question about it, you probably need quantitative validation. If you cannot describe the problem yet, start with qualitative exploration. For a comprehensive overview of available approaches, including both qualitative and quantitative options, see my guide on choosing the right research approach.

5 Core Qualitative Research Methods

Each qualitative method serves a different purpose. Choosing the right one depends on what you need to learn and where you are in the product lifecycle.

User Interviews

User interviews are one-on-one conversations where a researcher asks open-ended questions to understand a participant's experiences, needs, and motivations. They are the most versatile qualitative method and often the best starting point for teams new to research.

When to use them: Early discovery, understanding pain points, exploring how users think about a problem space, and gathering context that analytics cannot provide.

Sample size: 5-8 participants per user segment. You will start hearing repeated themes after the fifth conversation. That pattern repetition is a signal that you have reached saturation for that segment.

The difference between a productive interview and a wasted 30 minutes comes down to question quality. Avoid leading questions that suggest the answer you want. Instead, use prompts like "Walk me through the last time you..." and "What happened next?" For a deeper look at structuring effective conversations, see my guide on crafting effective interview questions.

Contextual Inquiry

Contextual inquiry combines observation and interviewing in the user's natural environment. Instead of bringing users to your office or a video call, you go to them. You watch them work, ask questions as they perform real tasks, and document the physical and social context that shapes their behavior.

When to use it: When you need to understand complex workflows, when users cannot accurately describe their own processes (which is more common than you think), or when the environment itself matters to the product experience.

What makes it different from interviews: In an interview, users recall and reconstruct their experiences. In contextual inquiry, you observe the experience as it happens. Users often develop workarounds and habits they no longer consciously notice. Watching them work reveals these invisible patterns. A nurse who says "the charting process is fine" might have three sticky notes on her monitor with shortcuts that compensate for a terrible interface. You would never learn that from a phone interview.

Usability Testing

Usability testing observes users as they attempt specific tasks with your product or prototype. The goal is to identify where users struggle, get confused, or fail entirely. It is evaluative research: you are testing whether a solution works, not exploring what to build.

When to use it: Before launching new features, after redesigns, when support tickets spike for a specific flow, or when analytics show unexplained drop-offs.

Five participants will uncover approximately 85% of usability issues, according to Nielsen Norman Group research. You do not need a large sample for usability testing because the goal is to find friction, not to measure it statistically. For detailed guidance on setting up and facilitating sessions, check out my article on running usability tests.

Diary Studies

Diary studies ask participants to log their experiences over days or weeks, capturing behaviors and emotions in the moment rather than through later recall. Participants record entries when specific events occur or at regular intervals, building a longitudinal picture of how they interact with a product or problem space.

When they shine: Diary studies are the best method for understanding experiences that unfold over time. Onboarding journeys, habit formation, seasonal usage patterns, and the slow erosion of satisfaction that leads to churn are all phenomena that a single interview session cannot capture. If you need to understand how something changes over weeks rather than minutes, diary studies are the right choice.

The trade-off: Diary studies require committed participants and take weeks to complete. They are higher effort than interviews but produce insights no other method can deliver. Keep the logging format simple (a quick mobile entry, not a detailed report) to reduce participant burden and increase data quality.

Focus Groups

Focus groups bring 5-8 participants together for a moderated discussion about a topic, concept, or experience. They generate ideas through group interaction and reveal shared language, cultural norms, and social dynamics that individual interviews miss.

When they work: Early exploration of attitudes and perceptions, testing initial reactions to concepts, and understanding the vocabulary users naturally use to describe a problem space.

When they do not work: Evaluating usability, making design decisions, or gathering honest feedback on sensitive topics. Group dynamics distort individual behavior. One confident voice can sway an entire room. Quiet participants self-censor. The loudest opinion is not the most common opinion. Use focus groups for generating ideas, not for validating them.

"When I asked 'who uses our product?' no one could answer." - Esmar, TrueProfile.io

That moment of silence, when a team realizes they have been building for a user they cannot describe, is where qualitative research earns its value. No dashboard or survey would have surfaced that gap. It took a direct question in a room full of stakeholders to reveal that nobody had done the foundational research to know who they were serving.

How to Plan a Qualitative Research Study

A structured planning process prevents the two most common qualitative research failures: asking the wrong questions and talking to the wrong people. The following five steps apply whether you are running a single interview or a multi-week diary study.

- Define your research question. Start with what you need to learn, not what method you want to use. "Why do enterprise users abandon onboarding at step 3?" is a research question. "We should do some interviews" is not. The research question determines everything that follows.

- Select the right method. Match the method to the question. Exploring a new problem space? Interviews or contextual inquiry. Evaluating a specific flow? Usability testing. Understanding behavior over time? Diary study. The decision framework above can guide this choice.

- Recruit the right participants. Your findings are only as valid as your participant selection. Define clear screening criteria based on who you need to learn from. Recruit from your actual user base when possible. For generative research, include a mix of current users, former users, and prospects to avoid survivorship bias.

- Execute with discipline. Prepare a discussion guide but stay flexible. Record sessions (with consent) so you can focus on listening rather than note-taking. Have a second team member observe to catch what you miss. Take note of emotional moments: frustration, confusion, delight, and surprise.

- Synthesize for action. Raw notes are not findings. After your sessions, identify patterns across participants. Group observations into themes. Translate themes into implications for the product. Share findings in a format your team will actually use, whether that is a one-page summary, a video highlight reel, or a direct conversation.

"Journey mapping is an output format for research, not a phase." - Christian Strunk

The pattern I see across teams that succeed with qualitative research is that they treat synthesis as the most important step, not an afterthought. The interviews are the easy part. The hard part is turning 10 hours of conversation into three clear insights that change what the team builds next.

Selling Qualitative Research to Stakeholders

Knowing how to do qualitative research is only half the challenge. The other half is getting organizational buy-in to do it at all. Leadership teams often view qualitative research with skepticism, especially in data-driven cultures that equate "real evidence" with numbers.

In my coaching experience, the most effective way to overcome resistance is to reframe the conversation from "we need to do research" to "we need to reduce the risk of building the wrong thing." Stakeholders who resist a two-week research sprint rarely resist reducing the chance of a failed launch.

Here are the most common objections and how to address them:

- "We do not have the budget." You do not need a budget to start. Guerrilla usability tests with five participants cost nothing but time. Customer support calls are free qualitative data sitting in your inbox. Start with what you have and build the case for investment with early wins.

- "We do not have time." Calculate the cost of your last failed feature. How many engineering weeks went into something users did not want? A single day of user interviews could have prevented that waste. The time spent on research is almost always less than the time wasted building the wrong thing.

- "We already know what users want." Ask the team to independently write down the top three user problems. Compare the lists. In most teams, the overlap is surprisingly small. That disagreement is the evidence that research is needed.

- "The sample size is too small to be meaningful." Qualitative research does not aim for statistical significance. It aims for pattern recognition. Five interviews that all reveal the same frustration is strong evidence, even without a confidence interval. Explain the difference between depth and breadth.

What you can accomplish at different investment levels:

| Budget | What You Can Do | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 0 EUR | 5 guerrilla usability tests, support ticket analysis, internal stakeholder interviews | Identify top 3 usability issues, surface unmet needs from support data |

| 500 EUR | 8-10 remote interviews with incentives, basic transcription tools, recruited participants | Deep understanding of one user segment, validated problem hypotheses |

| 5.000 EUR | Full research sprint: contextual inquiry, diary study, or multi-segment interview series with professional transcription and analysis tools | Comprehensive insight report, persona updates, prioritized opportunity map |

The ROI argument for qualitative research becomes concrete when you frame it as risk reduction. A product team of five engineers costs roughly 50.000 EUR per month in salary alone. If qualitative research prevents even one sprint of misdirected work (two weeks, approximately 25.000 EUR), the return on a 500 EUR research investment is 50x. That is an argument stakeholders understand. If you are looking for coaching support on integrating research practices into your team's workflow, explore my product coaching services for hands-on guidance.

Common Mistakes in Qualitative Research

Even experienced teams make predictable errors with qualitative research. Here are five mistakes I see repeatedly in coaching engagements, along with practical fixes.

1. Leading participants toward the answer you want. "Do you find this feature useful?" is a leading question. It signals the expected answer. Replace it with "Tell me about the last time you used this feature" or "Walk me through how you accomplish [task] today." The difference between a productive research session and a confirmation exercise comes down to question framing.

2. Talking to the wrong participants. Recruiting convenience samples (colleagues, friends, power users who volunteer) produces biased findings. Your most vocal users are not your most representative users. Define clear screening criteria before recruitment. Include users who struggled, users who churned, and users who almost bought but did not.

3. Skipping synthesis. Ten interview recordings sitting in a folder are not research findings. They are raw data. Without dedicated synthesis time (identifying patterns, grouping themes, translating to implications), you end up with anecdotes instead of insights. Block synthesis time on your calendar before you schedule the first interview.

4. Treating research as a one-time event. A single research sprint produces a snapshot. User needs evolve. Market conditions shift. Competitors change the landscape. Qualitative research delivers the most value when it becomes a regular practice, not an annual project. Even two conversations per week compound into a deep understanding of your users over a quarter.

5. Failing to connect findings to decisions. In my coaching experience, this is the most damaging mistake. Teams that do excellent research but store it in a slide deck nobody opens are wasting their effort. Every synthesis session should end with explicit decision implications: "Based on what we learned, we should..." If your research does not change what the team builds, refine your process until it does. For a broader framework on connecting research to validating customer problems, the customer discovery process provides a structured path from insight to action.

Final Thoughts

Qualitative user research is not about following a rigid methodology. It is about building a habit of direct contact with the people you are building for. Start with one method, run it well, connect what you learn to what you build, and expand from there.

The teams I coach that get the most value from qualitative research share one trait: they treat every user conversation as an opportunity to be proven wrong. They walk in hoping to learn something that challenges their assumptions, not something that confirms them. That mindset, more than any specific technique, is what separates research that drives great products from research that decorates slide decks.

Start small. One interview this week. Five next month. A regular cadence by next quarter. The compound effect of consistent qualitative research will transform how your team makes decisions.