Minimum Viable Product: Why Most Teams Build Too Much

TL;DR: Minimum Viable Product in 60 Seconds

- Core idea: An MVP validates your riskiest assumption with the smallest possible investment

- Biggest mistake: Teams build feature-complete products and call them MVPs

- Right-sizing tool: The MVP Sizing Framework (4 questions) to determine what to cut

- Key stat: 42% of startups fail because they build something nobody needs (CB Insights)

- Quality rule: Minimum means fewer features, not lower quality. Your brand standards still apply

- Bottom line: A good MVP takes weeks, not months. If yours takes months, it is not minimum

A minimum viable product is the smallest version of a product that lets you validate your riskiest assumption with real users. It is a learning tool, not a half-baked version 1.0. After coaching dozens of product teams, the number one mistake I see is not building too little. It is building too much. Teams spend months perfecting features that nobody asked for, then wonder why users do not stick around.

This guide breaks down what an MVP actually means, introduces the MVP Sizing Framework for right-sizing your experiments, and covers validation techniques by business type. Whether you are launching a startup or testing a new feature inside an enterprise, the principles are the same: build less, learn faster.

What Is a Minimum Viable Product?

A minimum viable product is the smallest version of a product that allows a team to collect the maximum amount of validated learning about customers with the least effort. The concept was popularized by Eric Ries in his 2011 book "The Lean Startup," though the term was originally coined by Frank Robinson in 2001. The MVP sits at the core of the Build-Measure-Learn cycle: you build the smallest thing, measure how users respond, and learn whether your assumption was correct.

To understand what makes an MVP work, parse the three words individually. "Minimum" means the smallest scope that still produces a meaningful signal. "Viable" means the product must actually work for real users. It does not have to be beautiful or feature-rich, but it must solve a real problem well enough that someone would use it. "Product" means it delivers value to a user, even if that value is narrow.

"An MVP is the smallest thing to learn the next most important thing." (Josh Seiden, co-author of Lean UX)

Josh's definition reframes the MVP from a product milestone to a learning milestone. The goal is not to launch something. The goal is to learn something. Research from Statsig and industry studies suggests that startups testing through MVPs reduce their failure risk by 60-70% compared to those that skip validation entirely. That makes the MVP one of the highest-leverage tools in a product team's toolkit.

What a Minimum Viable Product Is Not

The MVP is one of the most misunderstood concepts in product management. It is not a prototype, not a beta release, and not permission to ship garbage to users. Let me clear up the distinctions.

| Concept | Purpose | Users | Quality Bar | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototype | Test a design concept | Internal team, test participants | Can be non-functional | Figma clickthrough of a checkout flow |

| MVP | Validate riskiest assumption | Real target customers | Must work, can be rough | One-feature app that solves one problem |

| Beta | Test stability and polish | Early adopters, invited users | Near-production quality | Feature-complete app with known bugs |

| MMP (Minimum Marketable Product) | First version worth marketing | General audience | Production quality | Polished product you can charge for |

A prototype tests whether the design makes sense. An MVP tests whether the business assumption is correct. A beta tests whether the product is stable. An MMP tests whether the market will pay. These are different tools for different questions at different stages. Calling everything an "MVP" waters down the concept and leads teams to build too much too soon.

Minimum Scope, Not Minimum Quality

In my coaching experience, the biggest misconception about MVPs is confusing scope with quality. Shipping an MVP does not mean delivering a bad product. If you work at an established company with a design system, brand guidelines, and user expectations, those quality standards still apply. The "minimum" in MVP refers to features and scope, not to craftsmanship.

When I work with teams at companies that already have a product in market, I always emphasize this distinction: your users already have a quality baseline in their heads. A login screen that looks different from the rest of your app, a checkout flow that ignores your design system, or error messages that feel like a different product will destroy trust faster than missing features ever could. You always need to bear in mind the bare minimum of standards that you have, especially if you are a company that already has a product and is continuously iterating.

Cut features, cut scope, cut the number of user flows you support. But never cut the quality of what you ship.

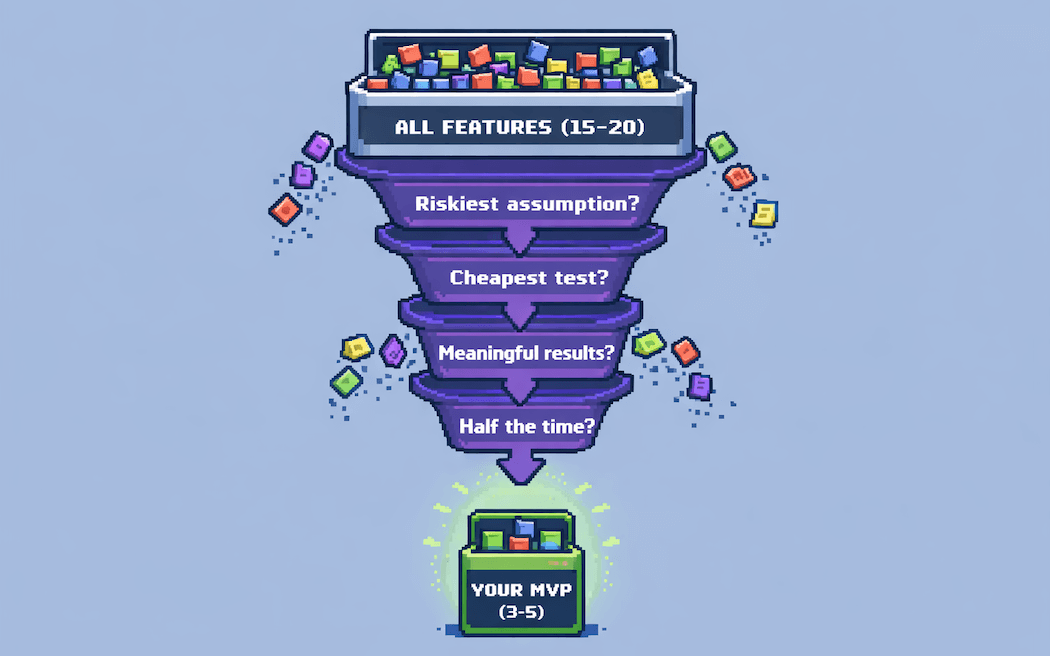

The MVP Sizing Framework

In my coaching experience, the most common sentence during MVP planning is "but we need this feature too." Teams arrive with 15-20 features they consider essential. They leave with 3-5 after working through these four filter questions.

Question 1: What is the riskiest assumption?

Every product is built on a stack of assumptions. The riskiest assumption is the one that, if wrong, makes everything else irrelevant. For a food delivery app, the riskiest assumption might be "people will pay a delivery fee for restaurant food." For a B2B analytics tool, it might be "product managers will switch from spreadsheets." Identify this assumption before building anything.

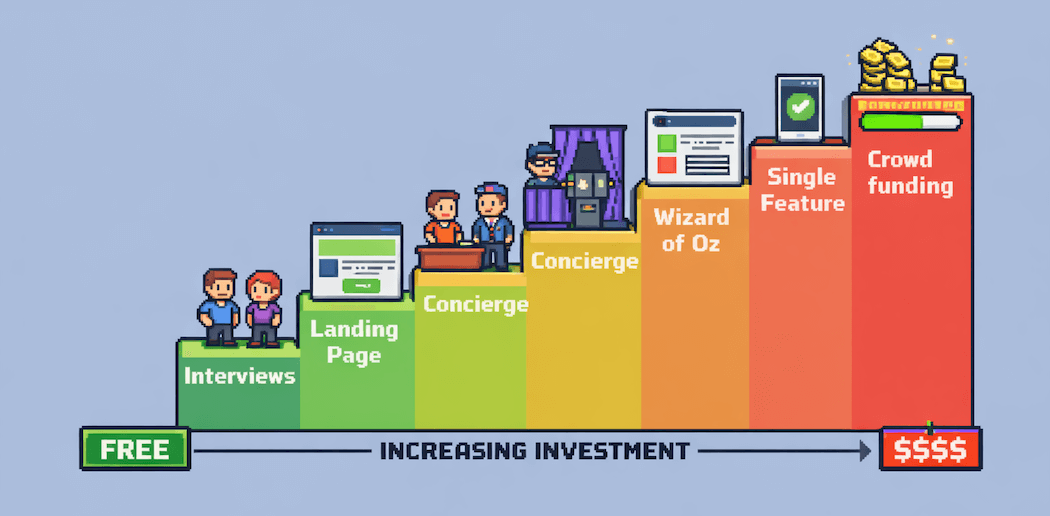

Question 2: What is the cheapest way to test it?

You do not always need to write code. The Validation Spectrum below shows six methods ranging from zero-code to full product. Pick the cheapest method that produces a reliable signal.

| Method | Time | Cost | What It Tests | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer Interviews | 1-2 weeks | Free | Problem existence, urgency | Early problem validation |

| Landing Page | 1-3 days | $100-500 | Demand, willingness to sign up | Market sizing, messaging |

| Concierge MVP | 2-4 weeks | Time only | Solution value, willingness to pay | Service businesses, complex workflows |

| Wizard of Oz | 2-4 weeks | Low-medium | Full user experience with manual backend | Automation-heavy products |

| Single-Feature MVP | 4-8 weeks | Medium | Core value proposition, retention | Software products with clear core feature |

| Crowdfunding | 4-6 weeks | Medium | Demand + willingness to pay upfront | Physical products, consumer hardware |

Question 3: What must be true for the test to be meaningful?

Define success criteria before you build. "People like it" is not a success criterion. "50 out of 200 landing page visitors sign up for the waitlist" is. "3 out of 10 concierge users convert to paid within 30 days" is. Without pre-defined criteria, teams rationalize any result as a success.

Question 4: What would you cut if you had half the time?

This question forces brutal prioritization. When I ask this in coaching sessions, the features teams cut are almost always features they never needed in the first place. If you can still test your riskiest assumption after cutting half the scope, you were building too much.

MVP Examples by Business Type

What an MVP looks like depends heavily on your business model. A B2B SaaS MVP looks nothing like a consumer app MVP. Here is how the concept applies across different contexts.

B2B SaaS MVP

B2B buyers have longer decision cycles and higher quality expectations. Your MVP needs to solve a real workflow problem, even if the solution is manual. A common pattern: start with a spreadsheet or a manual process before building automation. One team I coached ran their "AI-powered reporting tool" as a Google Sheet with manual analysis for 8 pilot customers. They validated demand in 3 weeks instead of 6 months of engineering.

Validation signals for B2B: signed letters of intent, pilot commitments, willingness to pay for early access, and champions who advocate internally for the product.

Consumer App MVP

Consumer MVPs depend on volume. You need enough users to generate statistically meaningful signals. The classic example is Dropbox: before building cloud storage, Drew Houston created a 3-minute demo video explaining what the product would do. The video generated 75,000 signups overnight. That validated demand without writing a single line of backend code.

Validation signals for consumer: waitlist signups, viral sharing, retention after first week, and organic word of mouth.

Marketplace MVP

Marketplaces face the chicken-and-egg problem: you need supply to attract demand, and demand to attract supply. The MVP solution is almost always manual matching. Start by playing the role of the marketplace yourself. Connect buyers and sellers manually. Validate that both sides get value from the transaction before building the matching algorithm.

"Customer development focuses on solutions that solve customer problems AND can be sustainably built." (Cindy Alvarez, Author of Lean Customer Development)

Cindy's point is critical for MVPs: the solution must be sustainable. A concierge MVP that requires 40 hours per week of manual work is not sustainable. Use it to learn, then build only what the data tells you to build. This validation process connects directly to achieving product-market fit.

| Dimension | B2B SaaS | Consumer App | Marketplace |

|---|---|---|---|

| MVP Timeline | 4-8 weeks | 2-4 weeks | 6-12 weeks |

| Validation Signal | LOI, pilot commitment | Signups, retention | Transaction completion |

| Quality Bar | Must solve real workflow | Can be rough, needs speed | Both sides must get value |

| Biggest Risk | Long sales cycles | Low retention | Chicken-and-egg problem |

| Best First Test | Manual service for 5-10 customers | Landing page + waitlist | Manual matching |

Why Most Teams Build Too Much

After coaching dozens of product teams through MVP planning, I have identified three root causes that consistently lead to over-scoped MVPs.

Fear of Launching Something Incomplete

Teams worry that users will judge them for a stripped-down product. The reality is the opposite. Users judge you for wasting their time with features they do not need. A focused product that solves one problem well earns more trust than a bloated product that does ten things poorly.

Stakeholder Feature Creep

Without a principled framework for saying no, every stakeholder request becomes a "must-have." The MVP Sizing Framework gives teams a structured way to push back: "Does this feature help us test our riskiest assumption? No? Then it is not in the MVP." Without that filter, scope grows in every meeting.

"There's nothing so useless as doing efficiently that which should not be done at all." (Rich Mironov, Product Management veteran with 30+ years experience)

Rich's quote is a reminder that execution speed does not matter if you are building the wrong thing. Many teams I work with are incredibly efficient at building features nobody needs. The MVP discipline forces them to validate before they execute. This connects to the broader practice of running product discovery before committing resources.

Confusing MVP with Version 1.0

An MVP is not your first release. It is your first experiment. Version 1.0 is a product you sell and support. An MVP is a tool you use to learn. When teams conflate the two, they apply version 1.0 quality standards to what should be a lightweight experiment, and the timeline balloons from weeks to months.

How to Define Your MVP Step by Step

Here is a six-step process for going from idea to MVP. Each step builds on the previous one.

Step 1: Start with the Problem

Validate the problem before building a solution. Interview 15-20 potential users. Ask about their current workflows, pain points, and what they have tried before. If the problem is not painful enough, no MVP will save you.

Step 2: Identify Your Riskiest Assumption

Write a testable hypothesis: "We believe [target user] will [expected behavior] because [reason]." The riskiest assumption is the one you are least confident about. Test that first.

Step 3: Choose Your Validation Method

Reference the Validation Spectrum table above. Match the method to what you need to learn. If you need to test demand, a landing page works. If you need to test whether users will pay, you need a concierge or single-feature MVP.

Step 4: Define Success Criteria Before Building

Write down what "success" and "failure" look like before you start. "If 30% of trial users complete the core workflow in the first session, we proceed. If fewer than 15% do, we pivot." Pre-defined criteria prevent post-hoc rationalization.

Step 5: Build the Smallest Thing (With Story Mapping)

The framework I rely on most when coaching teams through MVP definition is user story mapping. A story map visualizes the entire user journey as a horizontal sequence of activities, with user stories stacked vertically by priority underneath each activity. Drawing a horizontal line across the map creates your MVP boundary: everything above the line ships, everything below waits.

What makes story mapping powerful for MVP planning is that it forces teams to think in complete user journeys rather than feature lists. You cannot accidentally leave out a critical step because the journey makes gaps visible. At the same time, you can see exactly which stories to cut while preserving a complete path through the product.

Cut everything that does not directly test your riskiest assumption. If a feature is "nice to have," it is not in the MVP.

Step 6: Set a Time Limit

A good MVP takes 2-6 weeks. If your MVP will take longer than 8 weeks, it is not minimum. Go back to step 5 and cut more. The time constraint is a forcing function for scope. In my coaching experience, the best MVPs are the ones built under tight deadlines because the deadline forces teams to focus on what actually matters.

Measuring MVP Success

An MVP without measurement criteria is just a product launch. Here is how to know whether your MVP succeeded or failed.

Three categories of signals matter: engagement (are users interacting with the core feature?), retention (do they come back?), and demand (will they pay or commit?). The specific metrics depend on your stage.

| Stage | What to Measure | Green Light | Red Flag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Build (Landing Page) | Signup rate, email conversion | 10%+ visitor-to-signup rate | Less than 2% conversion |

| Concierge MVP | Willingness to pay, repeat usage | Users ask for more, offer to pay | Users disappear after first session |

| Single-Feature MVP | Activation, Day 7 retention | 40%+ activation, 20%+ Day 7 retention | Less than 15% activation |

| Revenue Test | Conversion to paid, willingness to pay | 5%+ free-to-paid conversion | Users love it free but will not pay |

"When I asked 'who uses our product?' no one could answer." (Esmar, Product Leader)

Esmar's experience is a warning sign that appears more often than you would expect. Teams build products without a clear picture of who the user is or how to measure whether they are succeeding. Before launching your MVP, make sure you can answer three questions: who is the target user, what behavior signals success, and what threshold triggers a go/no-go decision. You can track these signals systematically using lean analytics principles, and validate your user assumptions through structured customer discovery.

Common MVP Mistakes (and How to Fix Them)

These five mistakes account for the vast majority of MVP failures I see in coaching.

Mistake 1: Building for 6 Months and Calling It an MVP

If your "MVP" took half a year, it is a version 1.0 with an aspirational label. A real MVP is scoped to 2-6 weeks. Go back to the Sizing Framework and ask question 4: "What would you cut if you had half the time?"

Mistake 2: Testing with Friends and Family

Friends and family will not give you honest feedback. They want to support you, not crush your dreams. Test with strangers who match your target persona. Their indifference is the most valuable signal you can get.

Mistake 3: Measuring the Wrong Thing

Tracking downloads, page views, or signups without tracking engagement and retention gives you a false picture. 10,000 downloads mean nothing if 95% of users never open the app a second time. Focus on retention and activation, not vanity metrics.

Mistake 4: Not Killing the Idea When Data Says No

The hardest part of the MVP process is accepting when the data says your idea does not work. If your pre-defined success criteria are not met, the disciplined response is to pivot or abandon. The emotional response is to run another test, lower the bar, or add features. Fight the emotional response.

Mistake 5: Treating Every Problem as Needing an MVP

Not every hypothesis requires a built product to test. Some assumptions can be validated with interviews, surveys, or competitive analysis. The Validation Spectrum exists for a reason. Use the cheapest validation method that produces a reliable signal. Building code should be your last resort, not your first instinct.

Conclusion

Building less is a discipline, not a limitation. The MVP Sizing Framework gives you a structured way to cut scope without cutting learning: identify the riskiest assumption, find the cheapest test, define success criteria, and force prioritization through time constraints.

The teams I work with that succeed are not the ones with the best MVPs. They are the ones who learn fastest. They ship small experiments, measure honestly, and make decisions based on data rather than hope. That speed of learning is the real competitive advantage.

90% of startups fail, and 42% fail specifically because they built something nobody needed. The MVP exists to prevent exactly that outcome. If your team struggles with scope creep during MVP planning, my product coaching helps teams right-size their experiments and build a culture of validated learning.

What is the riskiest assumption behind your current product? Connect with me on LinkedIn to discuss your MVP strategy.